Ivo Andrić

| Ivo Andrić | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | October 9, 1892 Dolac (village near Travnik), Bosnia and Herzegovina, Austro-Hungarian Empire |

| Died | March 13, 1975 (aged 82) Belgrade, SR Serbia, SFR Yugoslavia (now Serbia) |

| Occupation | Novelist, short story writer |

| Nationality | Yugoslav |

| Notable award(s) | |

Ivo Andrić (Serbian Cyrillic: Иво Андрић) (October 9, 1892 – March 13, 1975) was a Yugoslav novelist[1][2], short story writer, and the 1961 winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature[3]. His writings dealt mainly with life in his native Bosnia under the Ottoman Empire. His native house in Travnik has been transformed into a Museum, and his Belgrade flat on Andrićev Venac host the Museum of Ivo Andrić, and Ivo Andrić Foundation.

Contents |

Biography

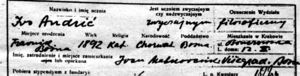

Andrić was born on October 9, 1892, to a Catholic family of Bosnian Croats[4] in Travnik, mahala Zenjak number 9, Bosnia and Herzegovina, then part of the Ottoman Empire, under control of Austria-Hungary. Originally named Ivan, he became known by the diminutive Ivo. When Andrić was two years old, his father Antun died. Because his mother Katarina was too poor to support him, he was raised by his mother's family in the eastern Bosnian town of Višegrad on the river Drina. There he saw the Ottoman Bridge, later made famous in his novel The Bridge on the Drina (Na Drini ćuprija).[5]

Andrić attended the Jesuit gymnasium in Travnik, followed by Sarajevo's gymnasium and later the universities in Zagreb (1912 and 1918), Vienna (1913), Kraków (1914), and Graz (PhD, 1924).[6] Because of his political activities, Andrić was imprisoned by the Austrian government during World War I (first in Maribor and later in the Doboj detention camp) alongside other pro-Yugoslav civilians.

Under the newly-formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (later the Kingdom of Yugoslavia) Andrić became a civil servant, first in the Ministry of Faiths and then the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, where he pursued a successful diplomatic career as Deputy Foreign Minister and later Ambassador to Germany. He was also a delegate of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia at the 19th, 21st, 23rd and 24th sessions of the League of Nations.[7] Andrić greatly opposed the movement of Stjepan Radić, the president of the Croatian Peasant Party. His ambassadorship ended in 1941 after the German invasion of Yugoslavia. During World War II, Andrić lived quietly in Belgrade, completing the three of his most famous novels which were published in 1945, including The Bridge on the Drina.

After the war, Andrić spent most of his time living in Belgrade and held a number of ceremonial posts in the new Communist government of Yugoslavia. He was also a member of the Parliament of Bosnia and Herzegovina. In 1961, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature "for the epic force with which he has traced themes and depicted human destinies drawn from the history of his country". He donated all of the prize money towards the improvement of libraries in Bosnia and Herzegovina. He was member of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts.[8]

Following the death of his wife, Milica Babic-Andric, in 1968, he began reducing his public activities. In 1969 he was elected an honorary member of the Academy of Sciences and Arts of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[9] As time went by, he became increasingly ill and eventually died on March 13, 1975, in Belgrade, SR Serbia, SFR Yugoslavia.

He was buried in Belgrade Novo groblje cemetery, in Alley of Distinguished Citizens.[10]

Works

The material for his works was mainly drawn from the history, folklore, and culture of his native Bosnia.

- The Bridge on the Drina

- Bosnian Chronicle[1] (a.k.a. Chronicles of Travnik)

- The Woman from Sarajevo[2]

Those were all released in 1945 and written during World War II while Andrić was living quietly in Belgrade. They are often referred to as the "Bosnian trilogy" because they were released at the same time and had been written near together in time. However, they are connected only thematically -— they are indeed three completely different works.

Some of his other popular works include:

- Ex Ponto[3] (1918)

- Unrest[4] (Nemiri, 1920)

- The Journey of Alija Đerzelez[5] (Put Alije Đerzeleza, 1920)

- The Vizier's Elephant[6] (Priča o vezirovom slonu, 1948; trans. 1962)

- The Damned Yard[7] (Prokleta avlija, 1954)

- Omer-Pasha Latas[8] (Omerpaša Latas, released posthumously in 1977)

His manuscripts and literary legacy is in custody of the Foundation he founded (Fondacija Ive Andrica) and Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts,[11]

Some claim that the works of Ivo Andric particularly his thesis "The Development of Spiritual Life in Bosnia under the Influence of Turkish Rule" have resurfaced as a source of anti-Muslim prejudice in Serbian cultural discourse.[12]

Classification

He is claimed as part of Croatian literature[3][13], Serbian literature[14][15][16][17], and Bosnian literature.[18] As far as standard language is considered, he wrote in Serbo-Croatian; prior to World War I he had been a believer in Yugoslav unity and Pan-slavism. However, it must be mentioned that Serbo-Croatian used to have two different subtypes - the Eastern standardization (spread in Montenegro, Serbia and partly in Bosnia and Herzegovina), and Western standardization that is common in Croatia and partly in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Andrić first used and write Serbo-Croatian Croatian form (Western) and later Serbian form (Eastern).[18]

Some characteristics of Eastern-standard are translating of foreign words, as well as some morphological aspects such as the construction of future tense: radiću (Eastern, I shall work), radit ću (Western).

There was also a more specific, and more fundamental, divide—that between ekavian and ijekavian standards of then-Serbo-Croat -- Andrić wrote in the ijekavian (standard in both Western standard Croatia, middle-of-the-road standard Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Eastern standard Montenegro) only in his youth. As a mature writer he wrote and published in ekavian (the official standard only in Serbia), even when depicting characters who live in Bosnia and who are quoted as speaking ijekavian in the dialogues, that stand out in otherwise ekavian text.

As far as first issue is considered, Andrić never used the translated equivalents of foreign words, as it used to be common in Eastern standard. As far as the second issue is considered, Andrić did allow Croatian publishers to change his ekavian works into ijekavian (unlike the Eastern, the Western standard was exclusively ijekavian), but he strictly forbade them from changing his future tense forms.

Serbian sources claim him as a Serbian writer, their arguments are following: 1. He mainly wrote in ekavian, standard existing only in Serbian language. 2. He declared himself as a Serb. In 1954 he stated ‘‘I stayed connected with the land of my birth, Bosnia, but the place of my life and my work was Belgrade.’’ [19] Also, when he got married at the age of 67, he declared himself as a Serbian [20]. 3. He was a member of the Serbian Academy of Science and Arts.

References

- ↑ Zoltan D. Barany, The East European Gypsies: Regime Change, Marginality, and Ethnopolitics (Cambridge University Press, 2001: ISBN 0521009103), p. 59.

- ↑ Rajko Đurić, Romanies and Europe: Romanies as Characters in European Literature (Council of Europe, 1996: ISBN 9287128553), p. 11.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Kaplan, Robert D. (1993-04-18). "A Reader's Guide to the Balkans". New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9F0CE7D91531F93BA25757C0A965958260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=all.

- ↑ "Croatia: Themes, Authors, Books". Yale University. 2001-10-01. http://www.library.yale.edu/slavic/croatia/literature/literature.html. Retrieved 2010-07-06. "Andrić was born of Croatian parentage on 1892, ..."

- ↑ Richard C. Frucht (ed.), Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture (ABC-CLIO, 2005: ISBN 1576078000), p. 568.

- ↑ "Andrić, Ivo," Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2005.

- ↑ List of Assembly Delegates and Substitutes - (A) from League of Nations Photo Archive at the University of Indiana

- ↑ SANU

- ↑ Akademija nauka i umjetnosti Bosne i Hercegovine, Honorary members.

- ↑ Ivo Andrić, Novo Groblje

- ↑ Ivo Andrić Foundation, Work.

- ↑ Ammiel Alcalay, Memories of Our Future: Selected Essays 1982-1999 (City Lights Books, 1999: ISBN 0872863603), p. 233.

- ↑ Yale University Library: Slavic, East European & Central Asian Collections, Croatia: Themes, Authors, Books.

- ↑ Sells, Michael (1996-07-03). "Of Bogomils, Race, and Ivo Andric". http://www.haverford.edu/relg/sells/postings/bogomils_race_andric.html.

- ↑ Enes Cengic, Krleža post mortem I-III. Svjetlost, Sarajevo, 1990. 2. part, pages 171-172 - here Andrić denies to be listed as a Croat

- ↑ Borislav Mihailović - Mihiz: Autobiografija - o drugima, Druga knjiga, page 137. BIGZ, 1995

- ↑ Hrvatski nobelovci (Croatian)

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Ivo Andrić". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2010. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/24035/Ivo-Andric. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- ↑ Andricećeva prijateljstva, Radovan Popović, page 217

- ↑ Andricećeva prijateljstva, Radovan Popović, page 240

- Ivo Andric, The Bridge on the Drina - The University of Chicago Press, 1977 - two biographical notes written by William H. McNeill and Lovett F. Edwards

External links

- Andric at NobelPrize.org

- The Swedish Academy secretary Anders Oesterling presentation speech

- Ivo Andrić Museum and Foundation

- Ivo Andric Revisited: The Bridge Still Stands

- Travnik memorial house (Portal of City of Travnik) (Bosnian)

|

||||||||